The first episode of Star Trek: Picard just premiered three days ago as I write this. There will be some spoilers, I won’t know how big they’ll be until I write them. You are warned.

I’ll prattle on a bit first to give some spoiler-free space before I get into Remembrance.

I’m not a fan of Star Trek: Discovery. I don’t hate it and they’ve done some good stuff, but as I said after the first episode, “This is not the Trek I’m looking for.” It’s a bit of a slog for me to get through the episodes. There was too much of a focus on war, but ultimately, it was the ethics that bothered me the most. I’m very much an old school Sci-Fi kind of guy and a fundamental part of that is that humanity is supposed to progress, to get better. The Federation and Starfleet have always represented that better version of humanity in Star Trek and even when they’ve lost their way, like in Insurrection, the plot revolved around the main characters setting it right. A first officer committing mutiny because she thinks she understands a situation better than her captain isn’t Trek. Even worse was the treatment of the tardigrade, which you have to compare to the Horta from the original series. In “Devil in the Dark,” Kirk, Spock, McCoy et. al. investigate a creature that’s killing miners on Janus VI. They take pains to understand the creature, discovering why it was attacking the miners and ultimately helping it. When the crew of Discovery encounters the tardigrade, they exploit the creature, even to the point of risking its life to basically make their ship go faster.

There are “reasons” and “context” for these actions and the Discovery crew eventually stop being horrible, but I think previous crews would have just dismissed the idea out of hand. Discovery got better by the second season, but it still leaves a bad taste. Like the first two Abramsverse movies, I’m left wondering how well the writers understand what makes “Star Trek” be Star Trek.

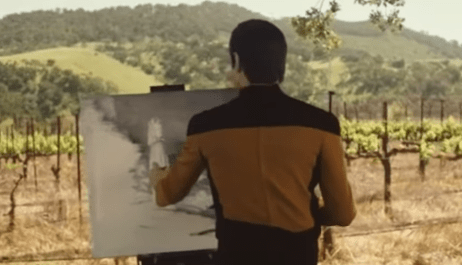

And here’s why I’m hopeful about this new series: it’s getting the ethics right. The universe is darker and there is some violence at the start of the episode that I found jarring in the context of a Star Trek episode, but the essential core is there. This was driven home in one particular moment for which I have to set the stage. Now-Admiral Picard has retired and is tending to the family vineyard in France. We’ve gotten some hints that his separation from Starfleet was contentious and we see that when he consents to an interview about the Romulan Supernova.

This event lead Jean Luc to step down from commanding the Enterprise in order to lead the rescue armada. Then, a group of synthetics attacked the colony on Mars, destroying the planet and the Utopia Planitia Shipyards where most Federation starships were constructed. Two subsequent decisions clearly bothered Jean Luc. The Federation banned synthetic humanoids and they canceled the rescue mission to Romulus. He resigned from Starfleet in protest, refusing to be complicit in the Federation turning its back on people in need. “The Federation understood that there were millions of lives at stake,” he told the interviewer. “Romulan lives,” she tried to clarify. “No, lives!” he replied. There it is. That is the core of Star Trek. We’re back to the classic situation, The Federation has lost its way and, in this case, it’s up to our titular character to put things right.

It is impressive how well constructed this episode is. The theme of memory is skillfully interwoven through the episode as one would expect for the pilot of a show built around a beloved character from a generation ago (not to mention an episode called “Remembrance.”).

There are also many, many so-called “Easter eggs.” You can check those out here.

And here. Thanks to Todd Egan and Forrest Meekins for the info and the links.

Really, calling these “Easter eggs” is an understatement. These are skillful callbacks to previous episodes and movies and they all point to what appears to be the central themes of the series; the rights of synthetic beings and the social evolution of the Romulans. Both were significant themes in TNG and they have philosophical and ethical heft. The callbacks to The Measure of a Man, one of the best and most significant episodes in all of Trek, were particularly acute. There’s an intriguing mystery developing involving both of these things and Jean Luc’s sense of right and wrong is right at the center.

One of the more intriguing allusions is the title of the stage-setting Short Trek “Children of Mars.” At first glance, the title seems straight forward; the story revolves around two school children who have parents on Mars. In rapid succession, we get to see their connection to those parents, a bit of their lives and then their devastated and devastating reactions as they watch as the synthetics’ attack on Mars unfolds in news reports. If you combine this with the fact that Romulus and Remus are not only the homeworlds of the Romulan Empire, but also the sons of Mars in Roman mythology, this short trek may be key to how the two primary threads of the series will weave together.

I think that a lot of the credit for the quality of this episode is due to Michael Chabon, Star Trek: Picard’s showrunner. I first encountered Chabon’s work 20 years ago when I read The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay. This novel centers around two young men who created a superhero back in the Golden Age of Comics, paralleling the story of Superman’s creators, Seigel and Schuster. The book is excellent; I’d recommend it to anyone with an interest in the genre. But, more than that, it is clearly a labor of love, very much like Star Trek: Picard. Chabon has been a fan of Star Trek since he was 10 years old and I expect that this new series will be a testament to how great new installments to venerable old properties can be when talented people who truly understand them are allowed to take the helm.

This now is the Trek I’ve been waiting for.

Bottom Line: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

References:

- Star Trek: Picard Spoilers Children of Mars Easter Eggs retrieved 27 January 2020

- Michael Chabon Steers Latest ‘Star Trek’ retrieved 27 January 2020